Content

75 years of the patent office in Munich, part 2

The patent office and Munich: The building, the arts and the media

"Legal protection again, at last" wrote the weekly "Die Zeit" after the opening of the German Patent Office in Munich. A "long-awaited line" had been drawn "under the embarrassing post-war lawlessness in the field of industrial property protection".

In fact, the large number of applications showed that there was a huge need for industrial property protection in the early stage of the "Wirtschaftswunder” (economic miracle). But the fact that now Munich should be the permanent seat of the patent office and no longer Berlin, where it had been for decades, caused long-lasting controversy even after the reopening of the office on the Isar river.

"Berlin, which housed the former Reichspatentamt, has not been forgotten either," continued the newspaper "Die Zeit"; “it is given a sub-office called "Deutsches Patentamt – Dienststelle Berlin" (Die Zeit, 16 February 1950) to support the work of the Munich office." On 1 February 1950, the sub-office was opened in the severely war-damaged building of the former Imperial Patent Office on Gitschiner Straße.

Big rush

"Big catch"

"It was a hard fight until this big catch of an office, for which many cities had scrambled for years, went to Munich."

(Süddeutsche Zeitung (SZ) vom 1.7.1952)

The first patent specification of the post-war patent office, published on 21 June 1950, was for the Linde company from Munich and had the number ![]() DE 800 001. The first utility model was registered under the number

DE 800 001. The first utility model was registered under the number ![]() DE 1600001 U for an "Anschlagsmaschine", i.e. a stirring device for bakeries of the Zumbült company from Beckum.

DE 1600001 U for an "Anschlagsmaschine", i.e. a stirring device for bakeries of the Zumbült company from Beckum.

As early as 2 December 1949, the "Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung" (FAZ) newspaper reported that a large number of IP applications had been filed with the patent office in Munich since it opened on 1 October 1949: 5,940 applications for patents (of which "only" 5,065 came from Germany!), 3,845 for utility models and 2,725 for trade marks (FAZ 2 December 1949).

Room wanted!

Soon the office needed more staff and the staff in turn needed more homes, so that the office placed ads to look for apartments for them (for reasons of economy with many abbreviations):

"German Patent Office in the Deutsches Museum is urg. looking for a large number of furn. and unfurn. rms by 3 Nov. Details immed. req. in wrtg or personally" (SZ 2 November 1949).

It soon became cramped at its provisional office in the library wing of the Deutsches Museum. While at the date of the establishment of the office, on 1 October 1949, the headcount was only 423, it had risen to 1,187 by 1951 – almost three times as many as before. In 1954, the German Patent Office had a staff of 1,809.

Allied influence

Even after the foundation of the Federal Republic, the Allies initially continued to exert strong influence on the legal conditions. In 1949, the FAZ was disappointed with the “Law No. 8 of the Allied High Commission in Germany on Industrial, Literary and Artistic Property Rights of Foreign Nations and Nationals” and stated: "It disadvantages German inventors and thus industry at large. (...) The rules governing industrial property must finally once again treat everyone equally. (…) It is not acceptable that the Germans should continue to be deprived of the fruits of their inventive work even within Germany, as has already been the case abroad through the confiscation of foreign patents” (FAZ 3 December 1949).

The former occupying powers also retained control over certain patents: “This weekend, the Council of Allied High Commissioners enacted a law on the control of German patents for security reasons. According to this law, patents that have any relation to the legislation of the occupying powers in the fields of prohibited and controlled research shall be submitted to the Allied Security Board for examination and control.” The Patent Office had to submit a bi-monthly report on patent applications in the fields of “prohibited and controlled research” (FAZ 19 December 1949).

Too many “Prussians” moving in

As was to be expected, the patent office quickly became an important economic factor in Munich: “6,000 people in Munich are living off the patent office,“ ran the headline of the "Süddeutsche Zeitung" newspaper at the beginning of 1950. The newspaper further reported that the office had placed orders of almost 1.5 million marks with more than 100 Munich companies.

According to the newspaper, however, the Munich residents were not pleased with the many "Prussians" who had moved in. “A lot of bantering and bitching was going on about the patent office from various quarters, because it had brought a part of the trained staff to Munich, which was indispensable for the rapid commencement of operations, and thus had increased the number of new arrivals by several hundred.”

However, at the same time the SZ pointed out that the Patent Office provided bread and work to its “retinue”, patent attorneys, patent law firms, photocopying offices, specialist publishers, etc., about 2,000 people in our city so that about 6,000 people including family members were economically dependent on the patent office (SZ 10 February 1950).

Berlin wants the office back

However, this fruitful relationship was threatened because the Berliners wanted their patent office back. In October 1949, representatives of Berlin’s industry demanded that the newly formed federal government relocate the patent office to Berlin as well as the supreme federal court, which had originally been included in the Basic Law.

In a letter dated 26 October 1949, Berlin’s mayor Ernst Reuter also demanded, not for the first time, that Federal Chancellor Konrad Adenauer “relocate all those authorities to Berlin that did not absolutely have to be located at the federal seat (Bonn)”.

On 18 October 1949, at the 13th cabinet meeting, Adenauer said it was necessary to establish a representation of the Federal Republic in Berlin. Adenauer said that “the heated Berlin atmosphere” was not the right place for the work of a supreme court. Rather, it would be better to consider relocating a higher administrative authority to Berlin. Even if the Federal Chancellor did not explicitly mention the patent office here – moving back to Berlin was still up in the air. And that even for a longer time.

More and more work for the office

In Munich, the office continued to grow rapidly. In February 1951, 150 patent applications were being filed daily, reported the SZ (10 February 1951). From early 1952 onwards, proper examination of patents was finally resumed at the Office.

Two years after the opening of the patent office, the "Süddeutsche Zeitung" reported that 106,443 patents, 72,778 utility models and 42,421 trade marks had meanwhile been applied for, including almost 20% from abroad!

“Some unwavering advocates of perpetual motion machine are still trying their luck. The patent office receives around 1,500 letters a day. The office, which is self-financing through its fees, has been able to pay as much as half a million marks to the federal government” (SZ 2 October 1951).

View into the "chamber of models"

At that time, it was customary to file a model of the invention with the patent office when applying for a utility model. The "Süddeutsche Zeitung" was allowed to take a look behind the scenes in 1952:

“The patent office’s chamber of models is indeed a hotchpotch of the most peculiar things. At first, you might think you're in a lost property office. But if you take a closer look, you discover that this pram has a double floor or that that crutch leaning against the wall has a spotlight and a taillight. (...)

The fact that there is still a lot of active inventive talent in industry is demonstrated by the busy public reading and search rooms of the patent office. Usually all the tables are occupied; “patent specifications, utility model registers and trade mark journals pile up in front of the designers, advertising managers and students” (SZ 1 July 1952).

In 1952, the 75th anniversary of the patent office was celebrated with a ceremony in the congress hall of the Deutsches Museum, attended by the heads of the patent offices of the United Kingdom, Greece, the Netherlands, Austria, Spain and Switzerland (SZ 2 July 1952). This was a clear sign that Germany was slowly regaining its old place in international relations, at least in the field of intellectual property.

Plans for a new building

A wish came true

"The relocation of the patent office from Berlin to Munich also fulfilled a wish that Bavaria had had for decades: to transfer a large higher authority of the German Reich or a higher federal authority to the Bavarian capital."

("Süddeutsche Zeitung" of 10 February 1950)

The number of staff had now tripled: “Today, the German Patent Office employs about 1,200 people,” wrote the "Süddeutsche Zeitung" (SZ 1 July 1952). The temporary facility in the Deutsches Museum, which after all had a rented area of 12,000 square meters, finally reached its limits.

The plans for a new building for the office quickly took shape. On 27 March 1953, the SZ reported that all tenants of the "Schwere-Reiter" barracks near Ludwigsbrücke had been given notice to leave. The building from 1811, also known as the "Neue Isarkaserne" (new Isar barracks), which was located directly opposite the museum on the other side of the Isar river, had been severely damaged during the war. According to SZ, 25 companies and some private individuals had to move out.

In August, readers of the SZ learned that the barracks had been almost completely demolished and that plans for the new building of the patent office had been completed: “The new building became necessary because the rooms in the library building of the Deutsches Museum, which had been rented by the patent office until 1958, no longer met the increased requirements of the office. When the DPA became operational in 1949, the expected number of patent applications per year was about 35,000. However, this number was surpassed by far: as early as 1950, there were over 53,000 applications, two years later about 58,000. The latest reports mention 60,000 patent applications, 25,000 applications for trade marks and 50,000 for utility models. Over the years, the number of staff had to be doubled. Next year the office will have as many as 2,000 civil servants and employees” (SZ 18 August 1953).

Ceremony with uncertainties

On 21 September 1953, the foundations were laid for the new building on Zweibrückenstraße. In July 1954, the topping-out ceremony for the first construction phase was celebrated. Was the question of the location of the patent office in Munich finally settled? No! According to the SZ report, confusing remarks could be heard during the ceremony:

The question as to whether the patent office should remain in Munich was cautiously touched upon by Ministerialdirigent Dr (Günther) Joel, who said that "here, too, the final decision can only be made once the borders that still cut through our fatherland have been removed".

At least the builders took it with humour. The foreman, Georg Rippert, said in his topping-out speech (according to the SZ of 12 July 1954):

"Das Patentamt kommt auf diesen Platz,

das früher gewesen ist in Berlin.

Vielleicht kommt´s später wieder hin.

Dann machen wir, wenn auch nicht gern,

das Haus halt wieder zur Kasern´."

(The poem is about the construction of the patent office on the Munich site and about its possible future return to its former location in Berlin. It continues that if the office was to return there, the builders would have to convert the building back into a barracks, albeit reluctantly.)

Federal cabinet has concerns

The concerns were justified, as a glance at the minutes of the ![]() 30. Kabinettssitzung of 28 April 1954 indicates. It discussed the submission of the Federal Minister of Finance on the construction of the new office building for the Patent Office in Munich (estimated costs: 22.7 million marks).

30. Kabinettssitzung of 28 April 1954 indicates. It discussed the submission of the Federal Minister of Finance on the construction of the new office building for the Patent Office in Munich (estimated costs: 22.7 million marks).

The Federal Ministers for All-German Issues and for Special Affairs expressed “serious concerns” with regard to the new building in Munich: “In view of political situation, the current timing was very unfavourable for starting work on this new building. It had to become apparent, at least externally, that this was only a temporary solution.”

State Secretary of Justice Dr Walter Strauß explained that the official building of the former Reichspatentamt in Berlin was damaged and obsolete, so that considerable sums had to be spent on refurbishment. Back then, it had been decided to choose Munich as its seat because the Bavarian government had made the most favourable offer, Strauß said. He was convinced that if Berlin were reunited, it would lose all interest in the German Patent Office in view of the fact that all relevant federal authorities would move in, said Strauß with remarkable foresight.

"Shortage of space no longer tolerable"

Strauß added that apart from that, there were quite a lot of visitors to the patent office. It would therefore be “hardly acceptable” for business and industry if the office were housed in Berlin. Moreover, it was intended to reach an agreement with Bavaria that the Bavarian Free State would take over the building if the patent office moved to Berlin. Thus the final decision on the seat of the German Patent Office would “not be prejudged”. In any case, Strauß continued, the new building of the patent office was most urgently needed, as the current cramped conditions were “no longer acceptable”.

In the course of the further discussion, the Federal Minister for Housing (Victor-Emanuel Preusker) asked whether there had not also been political objections to moving the office to Berlin, back then when the seat had been chosen, and whether these objections were not also still valid today. The Vice-Chancellor (Franz Blücher) confirmed that, back then, the dangerous political situation had been a determining factor for the choice of the seat of the patent office.

According to the Federal Minister of the Interior (Gerhard Schröder), the question of a possible later relocation of the patent office from Munich to Berlin was not so much a question of building costs but rather of the relocation of people working in and with the patent office. According to the minutes, he was not worried about finding appropriate use for the future new building of the patent office in Munich, at any time. The Federal Minister of Post and Communications (Siegfried Balke) was also of the opinion that the most urgent task was to ensure that the patent office was able to work. At present, the working conditions are “unacceptable”.

After the “vast majority” of the cabinet had voted in favour of the new building in Munich, it approved the proposal of the Minister of Finance.

In fact, the discussion about a return to Berlin considerably delayed the completion of the new building in Munich. At one time, the building activities had been suspended for one year, the SZ reported later (SZ 3 April 1959).

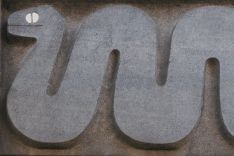

Sundial and snake

The new building was completed in three stages: The first stage was what is known as the atrium building with its five storeys on Zweibrückenstraße on the ground plan of the demolished barracks. A relief in the inner courtyard of the patent office above the exit to Zweibrückenstrasse still reminds us of it today.

On the outside of this passage there is a remarkable overdoor with the relief of a snake (as a symbol of wisdom and renewal) made of basalt lava. The sculptor Fritz Koenig created a striking fountain from Nagelfluh molasse conglomerate for the inner courtyard, whose facades are structured by plaster surfaces in grey tones.

A work of art visible from afar is located directly above the entrance on Zweibrückenstrasse. Here two large metal half-spheres are mounted at a lofty height. They refer to the famous Magdeburg experiment of 1656 by Otto von Guericke to prove the existence of air pressure.

However, the largest work of art (art in architecture) in the patent office is the sundial in the inner courtyard of the atrium building. Its dial extends over the entire floor of the yard - even if it is not immediately recognisable as such. The hand of the sundial is the corner formed by the shadows cast by edges of the two eaves of the building. The hand moves with the sun over the “dial” in the form of elongated figure-eight-shaped curves. The huge sundial also shows the zodiac signs and the months of the year.

"Dangerous state of overload"

In 1954, it was high time for this new building: “The patent office is drowning in applications,” was the headline of the SZ in July: “Federal Minister of Justice Fritz Neumayer said that one had to look ahead with concern to the further development of the German Patent Office (...) The number of incoming IP applications was constantly increasing” (SZ 31 July 1954).

“A large part of the business community is interested in a German Patent Office that functions well and quickly. Unfortunately, the current situation is far from satisfactory,” complained the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung newspaper (FAZ) – albeit with a great deal of understanding for the situation: “Two factors, in particular, have led to a dangerous state of overload. Firstly, for five years, from 1945 to 1949, the patent office was unable to work; all applications that had not been processed by the Reichspatentamt during the war and inventions made in the meantime were then transferred to the office for processing. Secondly, the office had lost the search file collected in the individual examination sections and must now slowly recompile it. In addition, the overall greater vitality of German industry in the Federal Republic places higher demands on the German Patent Office in Munich” (FAZ 24 May 1954).

More room!

In mid-1956 the "Süddeutsche Zeitung" announced the start of the second construction phase. At that time, a large part of the staff still worked in the building of the Deutsches Museum, but gradually more and more staff was moving into the new atrium building. The newspaper reported that the office expected to receive the millionth patent application since the founding of the office by the end of the year. And: “The number of patent attorneys and patent engineers based in Munich is constantly increasing” (SZ 28 June 1956).

So more room was needed – for administrative staff, books, documents: “At the patent office, numbers are of a considerable order of magnitude everywhere. The library, the largest technical library in Europe, comprises 360,000 volumes. 2.8 million patent specifications from the United States of America alone are available here. The Allies’ right of inspection and checking no longer exists, but instead there are again secret patents on inventions whose publication is not allowed for reasons of national security” (FAZ 1 October 1957).

However, above all, there was a need for space for the examiners and their work: “The soul of the patent office is the examiner,” wrote the FAZ in 1957, adding: “In Munich, five hundred of them are doing a responsible job in dealing with the sixty thousand new applications, a number that has remained almost constant over the last few years. The moment when the ticking time stamp of the patent office is pressed on the application documents marks the beginning of the thorny and sometimes painfully long path of the inventor up to the exploitation of his idea. If all goes well, he can generally expect that his application will be published after two years” (FAZ 1 October 1957).

"New monster building"

It took a total of six years, from 1954-59, until the entire new building was completed under the direction of the Landbauamt München. The ensemble was designed by two architects, Franz Hart and Helmuth Winkler – for both it was the biggest project of their professional careers. It consists of three components: the tower block along Erhardtstraße, the flat (“unattractive bunker-like” – SZ) patent search room in front of it, and the atrium building with its large inner courtyard on Zweibrückenstraße.

A characteristic feature is the change in structure and material of solid brick-perforated facades (atrium building), brick infill of a filigree reinforced concrete structure (tower block) and natural stone cladding (public search room).

The "Spiegel" magazine wrote about the “new monstre (sic!) building” of the patent office (no. 31/1959). The twelve-storey tower block was the highest office building in Munich at that time. It extends on the southern part of the site, parallel to the Isar river, and forms a structure dominating the urban landscape, which is visible from afar even today. Back then a normal feature, today a nostalgic highlight: the paternoster elevator in the tower block. It is one of the very few of its kind that has survived all renovations and the increasingly more stringent safety regulations and is still in operation today.

"Artistically ambitious modernity"

“The building is testimony to an architecture that follows the tradition of a context-conscious and artistically ambitious modernity that is typical of Munich architecture,” was the verdict decades later, when the complex was getting on in years and underwent general renovation. “The facades strike a balance between formal austerity and a richness in detail: The red infilled brickwork is characteristic of both parts of the building.”

“A new patent office,” the FAZ headlined on 4 April 1959: “The new building of the German Patent Office in Munich, built in six years for 26.5 million marks, was inaugurated by Federal Minister of Justice (Fritz) Schäffer, on Friday. The 200-meter-long and, for the most part, 38-meter-high building on the banks of the Isar river, opposite the Deutsches Museum, has 1,300 rooms for the more than 1,900 staff.” 56,000 square meters of office space were now available. “The secret patents are kept in a safe, a metre or more thick,” wrote the SZ (1 October 1959).

Books non-stop

One of the many special features of the new building was its automatic book conveyor system in the second basement of the tower block. The conveyor system was 98 metres long, ran through the entire library and fed a small freight elevator with 40 supporting frames. It was capable of transporting about 3,000 books and documents per day. The ordered works are issued at several locations of the tower block, that is on all eleven upper floors. The Siemens & Halske circulating elevator system had a total conveying height of 41.10 meters and was able to move as many as 510 special document conveyor boxes per hour.

TV detectives "Derrick" and "Der Alte" investigate at the patent office

This extraordinary book conveyor system was later to play a leading role in the TV crime series, which was shot at the DPMA in 1990: Episode 184 of the then enormously popular and internationally successful crime series “Derrick” was called “Deadly patent”. In a key scene, a dead body was transported on this conveyor belt. The murderer had put his victim – an examiner – onto the conveyor belt in the underground library, after committing the crime. Of course, detective Derrick (the name is a word mark protected by the DPMA; 1022323) solved the case with aplomb. At the end of the episode, the TV detective and the actor playing the president of the patent office were standing together on the rooftop terrace of the office philosophising about the abysses of the human soul.

Repeatedly, the DPMA has been a much sought-after film location due to the spectacular view of the Munich city centre from its rooftop terrace (the SZ marvelled on occasion of the opening “an ideal platform for photos of the city skyline“). The Munich skyline, which can be seen in the opening credits of the popular children’s series “Pumuckl”, was also filmed from the roof of the office building, as were several other such views in television series. Of the many films shot here over the years, only a few should be mentioned here: “Der Gesang der toten Dinge” (2008), an episode of the crime drama series “Tatort”, various episodes of the TV series “Der Alte” (The old fox) or the comedy “Ich Chef, du nix” (2005) with the actors of “Erkan & Stefan”.

Formerly controversial, today a listed monument

“This is where talent finds its patent,” the "Süddeutsche Zeitung" headlined its article on the completion of the new building. “Six years have passed since the ground-breaking ceremony on the site of the former "Schwere-Reiter" barracks took place. (...) Today’s inauguration of the complex of office buildings, built according to the exact requirements of the patent office, should ensure that the former Berlin-based office will remain in Munich” (SZ 3 April 1959).

However, not everyone liked the new patent office, which, according to SZ, was the largest administrative building newly erected in Germany at that time: “The architectural form of the 120-metre-long tower block along the banks of the Isar river was controversial. The residents of the surrounding houses, in particular, vehemently protested against the huge stone colossus. They had already opposed the brick front of the patent office during the first construction phase” (SZ 1 October 1959). Today, the building is considered a quality example of 1950s architecture and a listed monument.

Munich’s magnetic pull

It was not only numerous patent attorneys and law firms that settled in the patent office’s field of attraction. The “Institute for Foreign and International Patent, Trade Mark and Copyright Law”, which had been founded at the Ludwig Maximilian University at the suggestion of the President of the German Patent Office, Dr Eduard Reimer, became the “Max Planck Institute for Foreign and International Patent, Copyright and Competition Law” in 1966, now “Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition”. Munich also became the seat of the new Federal Patent Court (Bundespatentgericht) in 1961.

As the plans for a European Patent Office became more concrete in the 1960s, Munich, Bavaria, the Federal Government and, last but not least, the presidents of the patent office became very committed to bringing it to the banks of the Isar. And successfully so: In 1977, the European Patent Office was being built right next to the German office.

“But it is not only the institutions that make Munich the patent capital, it is also the companies that apply for patents,” the "Süddeutsche Zeitung" summed it up a few years ago. “With Siemens and BMW, two of the five busiest innovators are based in Munich. And as far as the patent applications received by the EPO are concerned, Munich outperforms all other German cities as well as London, Paris and Seoul” (SZ 16 September 2015).

Thus, a temporary sublet solution became Europe’s centre for industrial property protection.

The complete articles series

- Part 1: How it happened that the patent office is located on the banks of the river Isar and Munich became the centre of industrial property protection

- Part 2: The patent office and Munich: The building, the arts and the media

Pictures: DPMA

Last updated: 27 June 2025

Not only protecting innovations

Social Media